SALON DINNER SERIES, 2015-19

I created salon dinners based on the political and economic conditions of notable periods in art history (London in the 1730s; Tehran in the 1970s; Paris 1800-1815; Moscow 1917-1925; and New York 1870-1910). These dinners had several courses of food recreated from historical recipes, and each course was paired with a short lecture. Although they’re theorized and informative, dinners are also a way to reflect on the fact that art is a social industry. As all of us who have been to opening receptions or art fairs or fundraising galas know, art is about parties, and parties have snacks! If artists and their supporters are making what will become history-defining decisions over shared meals, the question bears asking, what do they eat?

I began this project because I was curious about how we got the art worlds that we have today. We all have complaints about the global contemporary art market and the institutions that support it—exclusion in the art world is structural and violent. Yet we still tell ourselves stories about the value of taste and connoisseurship, and stories about the naturalness of free market capitalism, but those things are neither innately good nor inevitable. Other art worlds are possible, and other art worlds have existed. How did they work?

The Gilded Age (1870-1910) was an age, much like our own, defined by rapidly rising wealth inequality. Massive fortunes, made in advancing technology fields like electricity, steel, and photography, funded the United States’s first large-scale philanthropic institutions, including art museums.

At the same time, a series of ethnological museums were also founded, like the Bucks County Historical Society and the American Museum of Natural History. The tension between the two 19th century museological methods, ethnological (featuring “peasants” and the colonized) and artistic (covering European traditions), comprised Gilded Age display systems for craft objects. Gilded Age newspapers expressed national anxieties also experienced today: labor strikes, financial panics, large waves of immigration, and technology developing at a pace far too fast for government regulation. In one of the key periods of US economic development, museums decided which objects were art and which were artifact.

Gilded Age New York:

A Wealth Inequality Dinner

Wellfleet oysters

Menu:

Huitres—Wellfleet

Potage—Soupe aux lentiles

Poussin—Muskee Sindh, Choux de Bruxelles à l’indienne

Rôt—Filet de bœuf, Pommes de terre à la Delmonico

Entrée Froid—Céleri, Têtes d’asperges en conserve en petites bottes

Glace—Jell-O

Cabinet Magazine HQ

Brooklyn NY

January 20, 2019

Photo

Filet de boeuf, pommes de terre a la Delmonico. Photo:

Guests listening to one of the lectures. Photo:

Jell-o serving

Kitchen: Christine Elliott, Cristina Marcelo, Sarah K. Williams, and Emily Gaynor

Guest lecturers: Sarah Lohman, Amy Schiller, and Dania Rajendra

This dinner, inspired by communal meals in Moscow and Petrograd during the first years following the Russian Revolution (roughly 1917-1921), facilitated group discussions about the wholesale reorganization of art and life during those tumultuous years.

The Russian Revolution was a chance for artists to destroy the hated old order of aristocratic patronage and build a bold new society. They moved from the easel to the street, endeavoring to shape the emerging consciousness of the proletariat while arguing fiercely amongst themselves about what exactly “proletariat art” should be.

Arts organizations like Proletkult (Proletarian cultural organization), Narkompros (the Commissariat of Enlightenment), and RABIS (the All-Russian Union of Art Workers) formed and evolved in quick time, working through new ideas and striving for cultural hegemony. In this rapidly changing art world, how did artists make work, and how did they make money? When given the chance to self-organize, which models did they choose (or invent)? In a time of widespread shortages, how did they manage to eat, and what did they eat when they could?

Soviet Salon: Dinner on the Centenary of the Russian Revolution

Rye bread

Menu:

Vodka

Ossetra caviar and blini

Cabbage soup

Kasha with sauerkraut

Gefilte fish and cabbage rolls

Apple cake and Soviet-style tea

Cabinet Magazine HQ

Brooklyn NY

November 7, 2017

Photo

Placesetting. Photo:

Soviet-style champagne

Sauerkraut fermenting?

Kitchen: Christine Elliott, Cristina Marcelo

Guest lecturer: Rebecca Ariel Porte

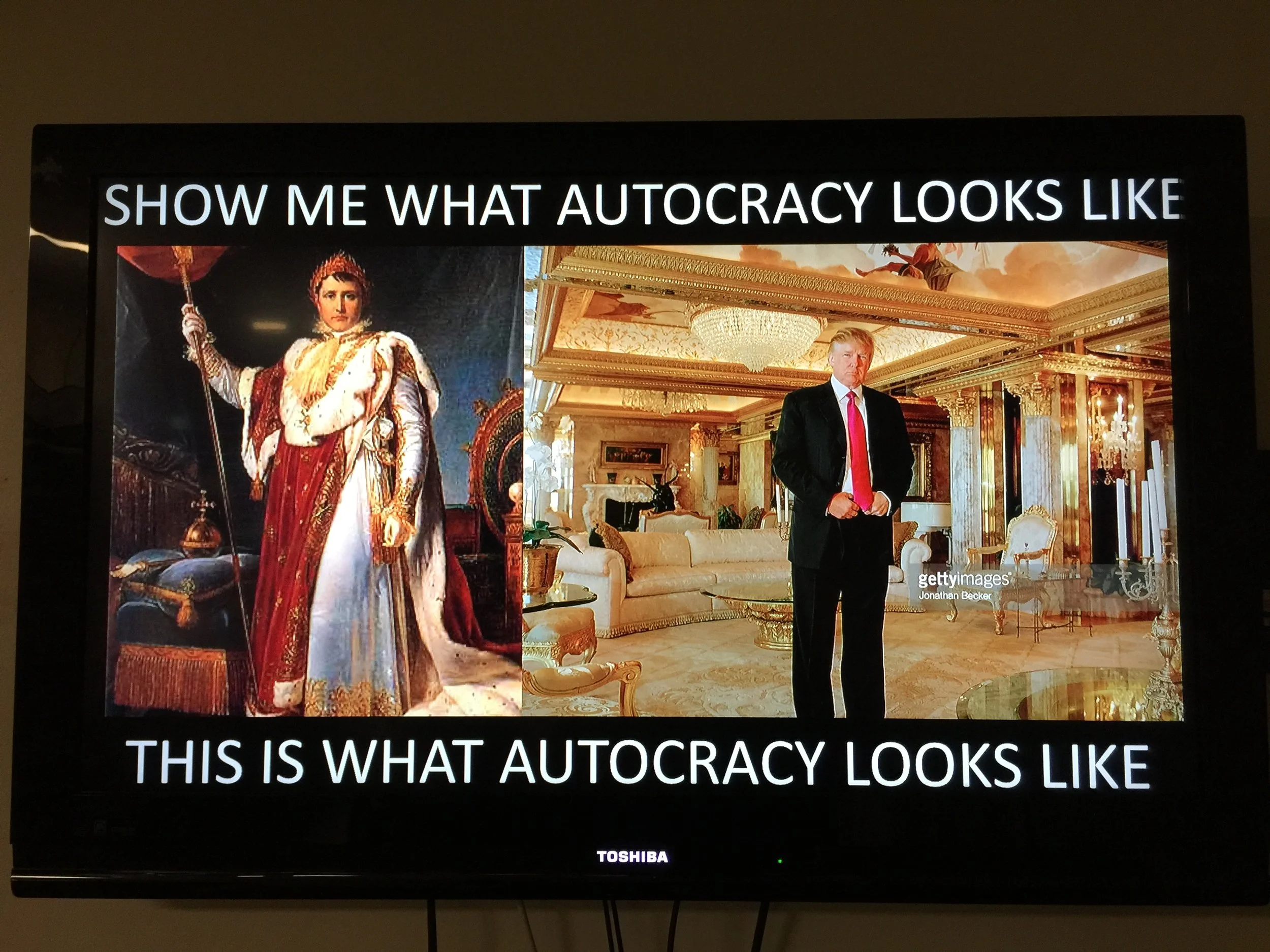

This salon, inspired by state banquets of Napoleon Bonaparte in his Tuileries palace, explored how art functions under an authoritarian regime.

Napoleon Bonaparte, a combative, proud, and popular leader, came to power in November of 1799, backed in a surprise coup by fellow reformists looking to make France great again. Over the next 15 years of his reign, he ruthlessly campaigned to extend the French empire, establishing his family members as dynastic rulers of his newly-won assets.

Napoleon was a master media strategist: he wrote bulletins to publicize his victories, commissioned favorable newspaper coverage, censored all anti-government voices, and produced propaganda on a massive scale. He especially relied on the spectacle and luxury of the imperial court to consolidate his new position in the world. Funded by the spoils of conquest, his ever-expanding government payroll employed artists and workshops that created statues and paintings of the emperor as well as decorative pieces marked with his personal brand.

In this salon dinner, we discussed the pageantry of the Napoleonic Empire and the people who produced it. Who were they? What did they make? How were they paid?

Napoleon Salon: Dinner in the First Empire

Tomato consommé

Menu:

Gougères

Tomato consommé

Salmon in hollandaise with asparagus

Lemon sorbet

Medallions of beef in sauce espagnole with haricots verts

Green salad

Pastries—Napoleon mille-feuilles, marzipan petit fours, lemon meringue tarts

Thank You for Coming

Los Angeles, CA

February 4, 2017

Photo

Kitchen staff. Photo:

Slide from the dinner.

Pastry course by Cayatano Talavera

Kitchen: Cynthia Su, Laura Noguera, Jonathan Robert, Carole Frances Lung, and Lauren Ross.